PANEL

The Online Magazine for Comic Stuff

by Billy West

November 11, 2013

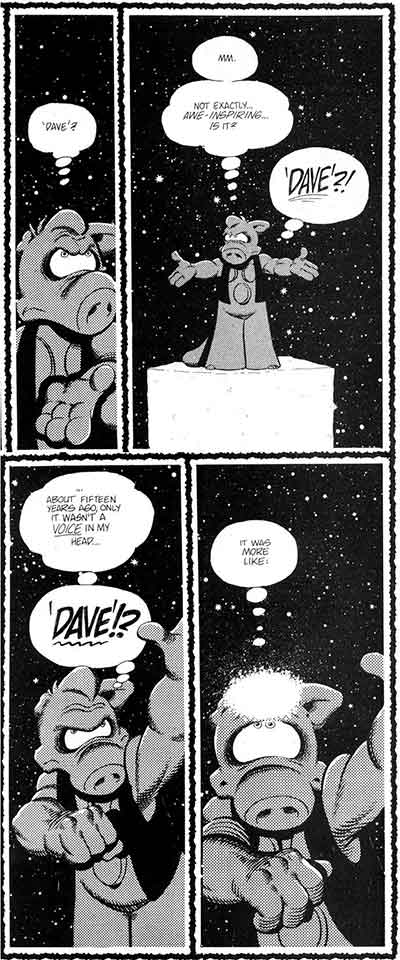

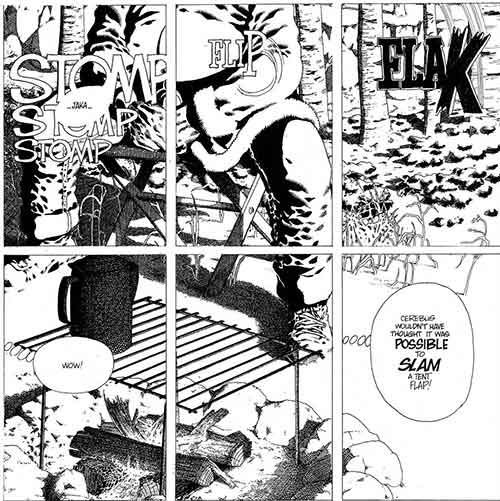

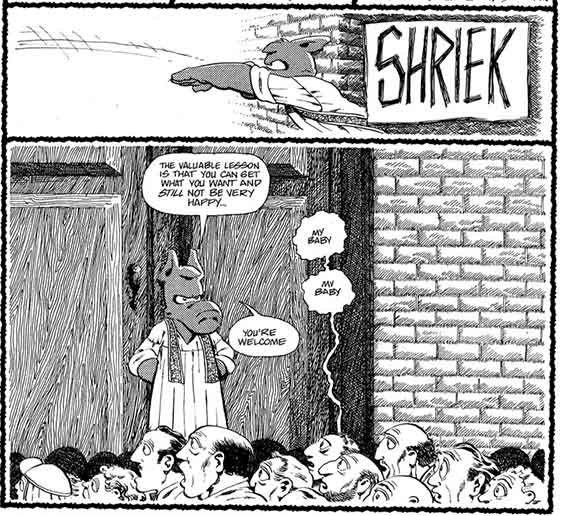

In December 1977, independent Canadian writer-artist Dave Sim launched his comic-book series Cerebus. This month, he completed it with the death of his titular character, in the long-promised 300th and final issue. Over 26 years and 15 hefty collected volumes, Cerebus, a foul-tempered anthropomorphic aardvark, has been a mercenary warrior, a politician, a religious leader and scholar, a revolutionary, a professional sports player, a bartender, and a comic-book fanboy, among many other roles. In telling his story, and laying out the larger social and political conflict that shaped his world, Sim has delved into broad satire, novelistic storytelling, and radical stylistic experimentation; at the same time, he’s used the back pages of his monthly issues to publish essays, boost other artists’ work, champion creators’ rights and tout self-publication, and interact at length with his readers and with other creators.

While admired for his long-term ambition, his artistic sophistication (helped in large part by his work partner and background artist, Gerhard), his technical innovation in areas like lettering and page design, and his commitment to creative independence, Sim has gradually become one of the most polarizing figures in comics, particularly over the controversial opinions he’s expressed in text pieces in Cerebus, and in lengthy essays like “Tangent,” his analysis and condemnation of “the feminist-homosexualist axis.” While preparing the 16th and final Cerebus reprint volume for publication, Sim recently agreed to speak with PANEL via fax about Cerebus’ origins, “Dave Sim Syndrome,” the Marxist-feminist sensibility, and where he’s headed next.

“…had become a 15-hour-a-day, six-day-a-week, Herculean task. At the age of 23, I actually thought I would be fine into my 50s doing a monthly comic book, but that I would let myself slack off by ending it at the age of 47. It’s a young man’s game.”

Why an aardvark?

You know, it’s really quite unbelievable to me that you have 4,000 words in which to cover the longest sustained narrative in human history, and your first question is “Why an aardvark?” What would your first question to Franz Kafka have been? “Why a cockroach?”

If Kafka had spent 30 years of his life writing one 6,000-page book about a man who turned into a cockroach, then maybe.

[Sighs.] Why an aardvark? Before there was Cerebus the comic book, there was Cerebus the fanzine. That’s how I met my ex-wife, Deni. I told her she needed a company name—the way Gene Day published Dark Fantasy through Shadow Press, which was what she wanted the ‘zine to look like: digest-sized. She asked her brother Michael and her sister Karen for suggestions. Michael suggested Vanaheim Press, Karen suggested Aardvark Press. I suggested combining the two. It turned out later that a boy that Karen had a major crush on—she was in high school then—had made a joke, posing his hand on the table so that the thumb and three fingers were balanced on their tips like legs, and his middle finger was extended like a snout. “Aardvark.” When you are a high-school girl and you have a crush on someone, these are the sorts of things that stay with you. So I drew a cartoon barbarian aardvark as a mascot for this fanzine publishing company. Later, when we realized that what Deni had intended to call the book was Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guarded Hades in Greek mythology, I told her we would just make Cerebus the name of the aardvark. The fanzine never got off the ground, so I decided to try drawing a sample comic page of Cerebus The Aardvark. And, for a number of months, that was all that existed: the page that turned out to be page one of Cerebus No. 1.

That’s interesting.

I’m glad you think so.

When you initially began Cerebus, did you intend it as a mouthpiece for social commentary?

I suppose that depends on how broadly you define social commentary. Red Sonja was the hot comic book at the time, beautifully written, penciled, inked, and lettered by Frank Thorne about a female Conan-type who wouldn’t surrender sexually to any man unless he defeated her in battle. When I did my parody, Red Sophia, I extrapolated that this poor, magnificent warrior woman was probably getting unbelievably horny waiting for someone to come along who could beat her. It does seem more resonant today now that the “ballsier” feminists, much to their consternation, seem to be having difficulty finding men who are interested in—or capable of—going mano a mano with them. At the time, it just seemed a funnier, racier version of the real thing. When Red Sophia whips off her chain-mail bikini top and says “What do you think of these?” and Cerebus deadpans, “They’d probably heal nicely if you’d stop wearing the chain-mail bikini.” I just hoped that it would sell enough copies that I could keep going. It wasn’t until two years in, when I switched to the monthly schedule and chose to attempt to do 300 issues, that that stopped being the primary motivation and switched to “How do you fill 300 issues of a comic book with something besides just sight gags and wordplay?”

“It’s a very strange book. And not strange in that “[family]” way that Harry Potter, from what I understand, is strange. “

At what point did you sit down to allocate the issues you had left?

First, I had to get over the disappointment of how little you could fit into a 500-page comic-book story. I had pictured doing the comic-book equivalent of War And Peace with 500 pages to work with. Originally, it was going to be the relationship between the political side of Iest and the religious side of Iest, spilling over from the one into the other. By the time I had figured out how many pages I needed to do an election campaign, election night, the deciding vote, and then six issues of Cerebus as Prime Minister, the book was over and I never even got to the religious side. That was why I doubled the length for Church & State, so it wouldn’t be just an A to B to C to D story. I’d be able to visit different parts of the city, and introduce “reads” and anecdotes of various figures that I had introduced. It still ate up pages like nobody’s business. So I learned to mentally scale back the books that I planned up ahead, learned to realistically assess what I could get across in 200 pages without having to rush everything. My best assessment now is that I hope I was able to produce, over the 6,000 pages, the comic-book equivalent of one Russian novel, as opposed to the 12 Russian novels I’d originally intended.